Legend

Legend has it that the name « Kitterlé », otherwise known as « Kütterlé, comes from the Schwab word Kuter, meaning big wild tomcat. The tomcat used to live in « Upper Saering » and its mischievous spirit could be sensed in the casks of the chateaux in the surrounding area. However, according to another version, « Kütterlé » was the name of a poor vine-grower from Guebwiller who was the first to be bold enough to set off up the hill (known locally as the “mountain”) and plant vines on it.

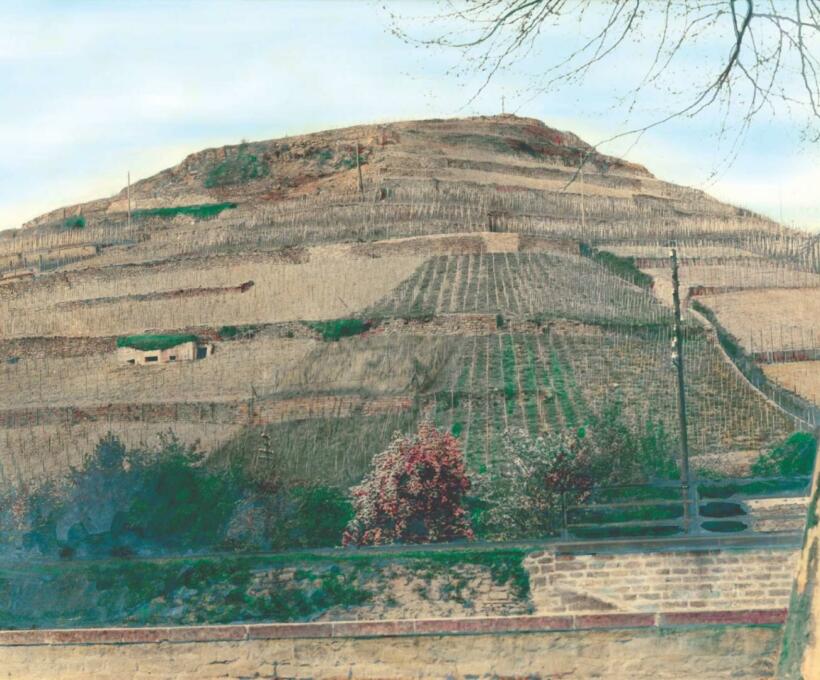

In bygone days there was a man called Kuter in Guebwiller, commonly called « Küterlé » because of his small height. He was a poor, intelligent, hard-working vine-grower who was unfailingly resolute. Not having many vines to cultivate, he decided to clear stony, rocky Upper-Saering. Many people laughed as they watched him perched on top of the rocks. Others felt sorry for him, but Kuter was not one to heed mockery. On the contrary, the more people commented and laughed the harder he worked. He extracted rubble stones from the split rock to build walls, then used the piled up soil to level terraces, one after the other. He then planted vines, which, level by level, took the hill by storm…

People continued to mock, saying « Let’s see what wine that’ll give ! » but the joke was soon on them. The hill was bathed in loving sunshine and the vines flourished for all their worth.

When Kütterlé produced his first wine, it was quickly compared to the fine wines grown in the surrounding areas. There was the fiery-natured Kessler, the ardent Wanne and, above all, the generous Saering. But after having weighed everything up, tasted and made their comments, the jury unanimously proclaimed that the last to come merited a place among the best.

Adapted from Abbot Braunn’s “Legends of Florival” 1886

History

Germanic mythology tells of Odin, the cunning magician god, who fertilised the Guebwiller valley. Wounded on the foot by a wild boar, he caused a flower to grow from every drop of his spilled blood. The flowers invaded the hillsides, blossoming brilliantly into grapes laden with divine blood.

The Kitterlé has been cultivated without interruption for more than 10 centuries. This terroir, mentioned as early as 1699, has always enjoyed an exceptional reputation. In the Middle Ages, Guebwiller was administered under the despotic rule of the Princes Abbé of Murbach. Any nobles or guilds that got in the way of their powers were expelled from the town or dissolved. In the 12th century, wine-growing made Guebwiller one of the most important towns in Alsace.

Wanne, Saering and Kitterlé vintages were shipped via Basel and Lucerne to Austria. Their reputation was such that unscrupulous merchants delivered harvests from the Swiss vineyards and elsewhere, passing them off as Guebwiller wine.

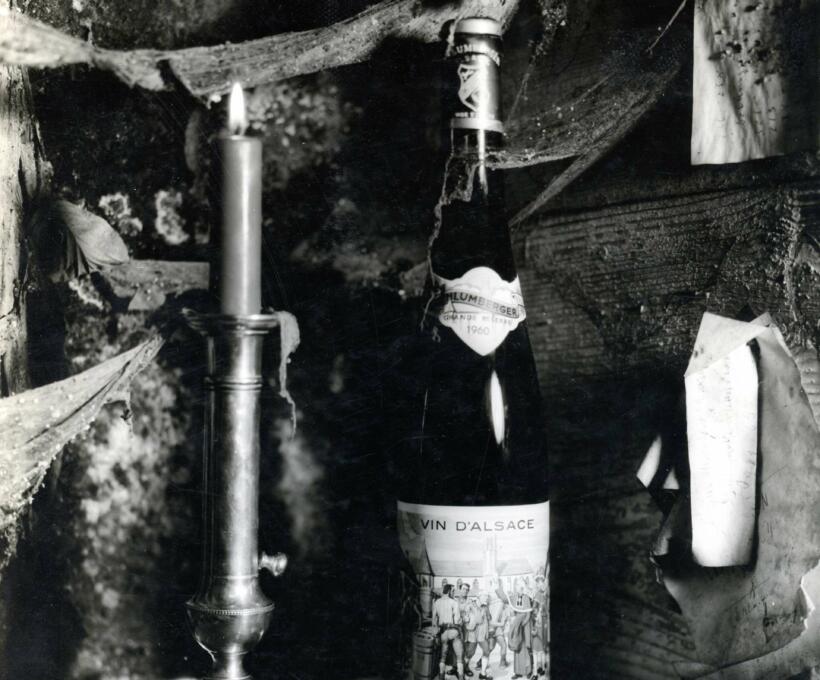

In the 17th century, to thwart the traffickers, the people of Guebwiller decided to affix a certificate of origin to each barrel of wine leaving their cellars. As evidenced by the letter dated 15 April 1667 from the town of Guebwiller to the town of Lucerne: “We decided to write to the gentlemen in Lucerne, because we have learnt that some buyers are allowing themselves to be lured into taking wines from Rouffach, Westhalten and Soultzmatt and reselling them as Guebwiller wines, and to declare that from now on these wines will be accompanied by a Ladtzettel or certificate of origin”. They thus became the forerunners of the “Appellations d’Origine Contrôlée” ….

(Taken from Claude Muller’s book « Alsace wines – History of a vineyard)

In the 19th century, the Annuaire Administratif du Haut Rhin (1854) stated that “particularly renowned […] are the gentile wines from Guebwiller, known as Kitterlé, which in certain circumstances take on a taste somewhat similar to the fruit of the rowan or hazel tree, giving them the names Eschgriessel and Hasselnusser. The wine from the same place, made from the ollwer grape, is reputed to prevent the formation of gravel, and is even said to cure those affected by this disease.

The deliberations of the Colmar town council (1837) provide the following information: “It is clear that the vineyards of Colmar, located on the plains, cannot be compared to those in the mountains … A “schatz” there sells for barely 800 francs, whereas in Guebwiller a “schatz”, which is seven ares in size, sells for up to 3,000 francs. The products of the best communes in the vineyard are far superior in quantity and quality to those of the first class of Colmar. We cannot (therefore) allow the valuations of the vines in the cantons of Rouffach, Ribeauvillé and Guebwiller to be so close to those of the poor vines on the plains”.

(Extracts from Claude Muller’s book “Les vins d’Alsace – Histoire d’un vignoble”)

While manufacturers from Switzerland and Mulhouse were buying up the former church estates to set up their textile factories, the wine industry was going through a rough patch due to poor sales of wine and a shortage of day labourers. Many people preferred to go and work in factories rather than continue to toil on the slopes of the Ober and Unterlinger mountains. The arrival of mildew and phylloxera exacerbated the situation.

The difficulties faced by the winegrowers were a godsend for the city’s new masters. The industrialists bought the best of the vineyards, starting with the good vintages that were sold as national property”, says G. Bischoff. One of them, Nicolas Schlumberger, began his conquest of the land by acquiring 20 hectares of vines in 1810. By the end of the 19th century, he owned 40 hectares. His estate was then one of the largest in the region. Among his descendants were some inveterate winegrowers: in 1910, Ernest Schlumberger, Nicolas’ great-grandson, undertook the complete reconstruction of the Guebwiller vineyards. Fifteen years later, his “remembrement” avant la lettre was completed with the acquisition of 2,500 new plots. The Schlumberger estate now covers more than 130 hectares of vines. It was the largest in Alsace and one of the largest in France.

A new era began for the Florival vineyards. It was marked by both industrial capitalism and a return to tradition. Plots were grouped together to form homogeneous units, containing only the grape varieties best suited to the soil and climate. Fifty kilometres of supporting walls were rebuilt or restored. The immense pink sandstone walls that support the Kitterlé terraces stand like the protective ramparts of the “garden of delights”.

Victor Canales Synvira